Background

Grosvenor Clive & Stokes is a specialist international executive search and advisory services firm with a long heritage in the energy sector. For over fifty years we have worked across the Oil & Gas value chain and in the Power, Renewables and Nuclear sectors for developers, E&P companies, power generators and utilities. Our involvement across the development lifecycle from initial fund raising to project development and operations gives us a unique insight into the activities of the industry. This is complemented by a number of our partners who have spent significant parts of their career in senior roles in the energy business, thereby bringing a wealth of knowledge and experience to the firm.

During the last two decades, we have undertaken many assignments in the North Sea working in the oil and gas upstream arena as well as the power and renewables sectors. Our clients range from multi-national and integrated energy companies to state power utilities and independent oil companies. Our work has included projects to find General Managers and their Leadership Teams as well as Heads and senior managers for all the technical, commercial and support functions.

Over the past few months, Grosvenor Clive & Stokes has sought the views of a broad cross-section of energy industry executives to gauge the impact of the current oil price volatility. This document distils those conversations into a review of the current thinking and takes into account data from other sources including The Wood Report and statements from the OGA and industry bodies.

The Author

Tim Shingler has worked in international Upstream Oil & Gas recruitment since 2003 specialising in senior subsurface and commercial appointments. His clients include a wide range of energy companies from global multinationals to the independent oil producers. He also has a strong relationship with the Oilfield Services industry and the Consulting sector, where he has a particular expertise in recruiting for specialist advisory firms operating in Exploration & Production.

Tim has a truly international network and client base, having worked successfully on assignments in Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Australia as well as in Africa and the FSU.

Prior to his career in executive recruitment, Tim spent many years working in the oil industry, firstly with Shell UK Exploration & Production, then as an oil analyst with James Capel & Co. and latterly as the Director leading the Petroleum Service Group at Arthur Andersen. Tim is a member of the Energy Institute (EI), the Petroleum Exploration Society of Great Britain (PESGB) and the SE Asia Petroleum Exploration Society (SEAPEX).

ths@grosvenorcliveandstokes.com

+44 (0) 7785 772649

Executive Summary

The UK sector of the North Sea is a highly productive arena for the international oil and gas industry and has attracted companies for the past fifty years. Oil and gas have been produced from a range of reservoirs utilising fixed and floating facilities. The industry has created a world-class workforce which has been exported around the globe. Due to the extreme weather conditions prevailing in the North Sea, the industry has been at the forefront of both technological development and safety regulation.

However, as a mature and challenging environment, the region has suffered from the dramatic fall in oil price which has put pressure on all operators to reduce costs, slim down the work force and investigate early decommissioning as fields mature and costs increase.

The government has reacted to the decline in production by requesting Sir Ian Wood to investigate the issues facing the industry. His report recommended, amongst other things, the establishment of the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA) to help guide the sector towards the maximisation of economic recovery in the UK North Sea.

The following points are highlighted:

- The North Sea has been a major contributor to HM Treasury over the past forty years

- Oil and gas production has been a major contributor to the security of supply for the UK for decades and still produces over 50% of the nation’s demand

- A substantial number of jobs have been created for the country including a cadre of world class expertise which has subsequently been exported to all parts of the global energy industry

- The Wood Report on Maximising Economic Recovery (MER) from the sector made a number of key recommendations which included the establishment of the OGA

- The OGA is working to develop a stronger, more efficient and more robust industry in the UK to ensure the future of the North Sea

- The current challenge for the industry is to produce hydrocarbons for less, as the oil price is expected to remain low for the short to medium term

- Collaboration between operators and service providers is fundamental and will play a critical part for the future of the North Sea industry

- The industry must be more imaginative and flexible in the future in order to reduce costs, improve efficiency and maintain or increase production.

- Bank and Private Equity funding is available for strong management teams which provide solid business plans that are robust in a depressed oil price environment

- Time is of the essence and the industry and the regulatory bodies must act to ensure that the North Sea has a long term future.

- We believe that production from the UKCS is an important national asset. A combination of initiatives including cost reduction, collaboration, investment, consolidation and ‘smarter production’ approaches can safeguard its future but these actions must start now.

Setting the Scene

The United Kingdom Continental Shelf (UKCS) is the area, as defined by international law, over which the UK Government has ownership and regulatory powers. It has been a major area for exploration, development and production of oil and gas reserves since the mid 1960s when the first licences were issued by the UK Government (Ministry of Power). This followed the signing of the Continental Shelf Act of 1964. The Act set out the terms for licensing of the North Sea for companies to apply for licences covering standard UKCS blocks. Each block is 12’E x 10’N producing 30 blocks in a standard quadrant. These quadrants are each, one degree latitude by one degree longitude. Each block covers an area of approximately 250 sq. kms.

The first round of offshore licensing in 1964 resulted in some 53 licences being awarded covering a total of 348 blocks to 31 companies. These blocks were primarily in the southern North Sea. Interest in the southern North Sea had been generated by the discovery of the giant onshore Groningen gas field in 1959 by Shell. The field is situated in the Northeast of the Netherlands and is still Europe’s largest natural gas field. The field lies in the Southern Permian Basin which extends from the eastern coast of England to Poland. It is this geological feature that excited oil executives at the time and spurred on the exploration for gas in the UK.

As a footnote: gas had been discovered and produced in the late 19th century in southern England at Heathfield. Oil was produced from the East Midlands (Dukes Wood and Eakring) and the northwest at Formby, to provide oil for the Royal Navy in the Second World War. The Eakring & Dukes Wood fields produced over 2.2 million barrels of oil for the war effort and by 1964 had produced over 47 million barrels before a single North Sea well had been drilled.

Since 1964 a total of 28 offshore licensing rounds have been held, covering all areas of the UKCS in the North Sea, Channel, West of Britain and West of Shetlands. The results of the 28th Round of Seaward Licensing were announced in November 2014, by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). A total of 134 licences covering 252 blocks were awarded making the round one of the most successful in the history of the UKCS. However, these applications were made before the oil price crashed!

In production terms, the first commercial gas field to come on-stream was in 1967 with West Sole operated by BP while the first oil field on-stream was the Argyll field in 1975 operated by Hamilton Brothers. A significant number of oil and gas fields have been discovered and developed (over 300) providing the UK Treasury with significant revenue through a range of taxes. UK oil production peaked in 1999, producing over 2.7 million barrels per day (MMbpd). The UK had been self-sufficient since the early 1980s but returned to being a net importer during 2004.

Over the years, the UKCS has seen a number of world-class fields developed and produced including Brent, Forties and Ninian (all +1 billion barrel oil fields) whilst Leman, Inde and Morecambe are world-class gas fields.

The North Sea has seen some of the most advanced technology used to find and extract hydrocarbons with the UK being recognised as one of the global centres of excellence for both skills and equipment. Due to the inhospitable weather conditions, the region has also seen the de-manning of platforms as technology and computer operated facilities have reduced costs and improved efficiency.

The Current Situation on the UKCS

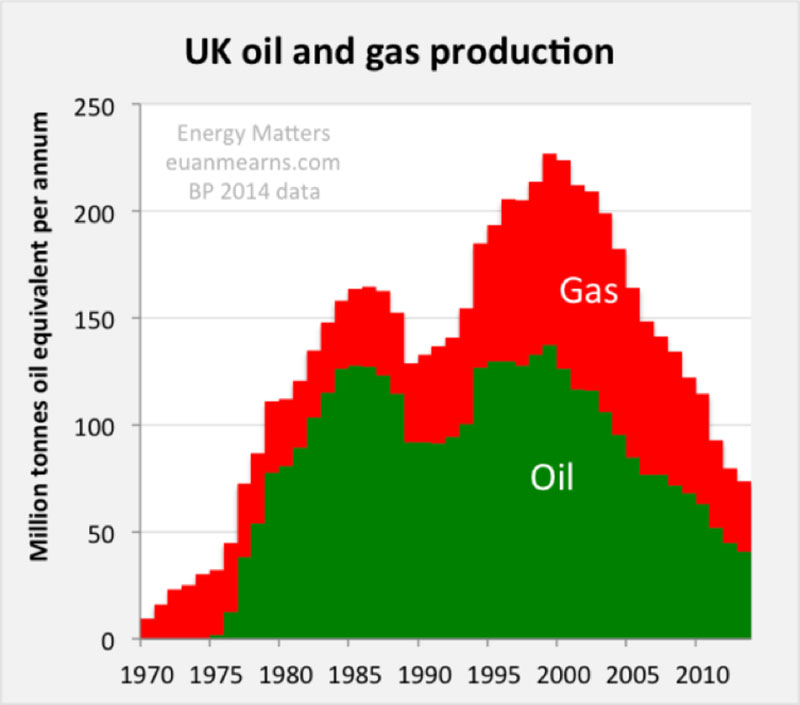

As new commercial reserves become more difficult and expensive to find, the region has seen a decline in exploration activity for some years and a significant fall in the production of both oil and gas since 2000 (see Figure 1 below).

Fig. 1 – North Sea oil and gas production profile from 1970

Courtesy of Gas Matters and BP

As other provinces offer higher potential rewards and, in some cases, better fiscal conditions, the UKCS is losing investment and interest. For example, Norway has seen a continued good level of exploration activity and production levels as the government has made efforts to retain players and allow exploration costs to be part funded by tax relief. However, this has promoted the drilling of wells with low success ratios.

North Sea oil and gas production has been of significant importance for the UK providing revenue to the Treasury, security of supply through nearly half a century and significant employment in the high-tech and skilled sectors. It is estimated that over 450,000 people are employed by the North Sea business.

Production has come from over 300 fields in the sector and despite the fact that production of oil and gas are both declining, they still provided more than 50% of the UK’s demand in 2014. Oil production is scheduled to rise slightly in 2016 and then continue to decrease over several decades. However, this decrease could accelerate if new fields and exploration drilling are adversely affected by the lower oil price. As the level of drilling continues to decline, new discoveries will not be made and the pipeline for the future will be severely affected while lower oil prices prevail. This may also result in further unemployment and the loss of key technical skills from the industry.

A total of only 13 exploration wells were spudded in 2015 whilst 14 exploration wells were spudded in 2014. Appraisal activity was limited to 13 wells in 2015 recording the lowest level of E&A activity for some decades. The recent 28th Round of Offshore Licensing was deemed a success but only five firm wells were offered with a further four as contingent. It is unlikely that the level of E&A drilling will climb in the near future although the OGA is exploring methods to stimulate activity. Recent drilling activity is a long way off the record level of 157 exploration wells drilled in 1990.

The UK North Sea has seen many of the majors reducing their investments and selling off older and smaller fields as well as infrastructure. This has provided opportunities for smaller companies to acquire assets, working them harder and cheaper to increase value and delay the decommissioning of platforms.

The issue facing many of the smaller players is that these companies borrowed significant amounts of money while the oil price was high (+US$100). After the oil price crashed in late 2014, repayments were difficult to make. Today, debt is high and many companies established to produce from older fields are now struggling to survive.

In addition to lower income, the cost of operating and maintaining older platforms and infrastructure has risen adding extra pressure to operators’ balance sheets. There are fields in the region that are losing money at US$30 per barrel. As a consequence, many operators are reviewing the future of their assets and shutting–in fields or decommissioning pipelines. This has a knock-on effect on some smaller fields which rely upon the larger fields for processing and export facilities.

In an effort to find some answers to the falling levels of interest and investment in the region, the UK Government asked Sir Ian Wood to review the industry’s needs, the role of the regulator and the tax take. He published his review ‘UKCS Maximising Recovery Review: Final Report’ in February 2014. It made a number of recommendations including the formation of a new regulator with more powers. It also identified the need for the new regulator to work closely with DECC and HM Treasury.

This report was written and published months before the oil price crash in late 2014. For many in the industry, these recommendations were unfortunately too late in the game and demonstrate the lack of an effective long-term energy policy in the UK. In April 2015, the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) was established. Its main goals are to increase investment and maximise economic recovery from the region, increase collaboration and co-operation and, help resolve disputes between companies. Many of these issues have fallen under the authority of DECC but with limited resources and high levels of work, its effectiveness has been restricted.

However, while the Wood report made important recommendations, it did not emphasise the key role of the oilfield services and contracting companies in the future of the sector. These companies are global and play a significant role in technology advances as well as operating fields on behalf of the operating companies. Therefore, it is essential to include these companies in all future decisions.

The oil price has played a critical role in the process of providing opportunities for new players when the oil price was high and money was both cheap and accessible. Now that the oil price is significantly lower, what opportunities does the region now offer?

As can be seen from the above graph (Fig 1), UK production is declining sharply and likely to continue to decline in the future albeit slightly increased in 2015. This could well be hastened by the premature decommissioning of fields by the impact of low oil price. Operators need to reduce OPEX in order to keep fields working; if this is not achievable then loss-making fields will be shut as has been demonstrated recently by the Dunlin field in the Northern North Sea (NNS). It is not expected that the price will increase considerably in the near term.

As infrastructure ages and production declines, maintenance cost continue to rise, adversely affecting the costs of operations. In mitigation, costs could be shared where a number of fields are produced through jointly owned facilities and export routes. Costs could also be reduced by using the latest technology in recovery methods to increase field life. However, the latest technology may be too expensive for limited field life. In consequence, closer co-operation and collaboration is required amongst government, oil companies and the service industry to ensure that the UK North Sea continues to provide hydrocarbons efficiently and economically.

The Effect of the Oil Price

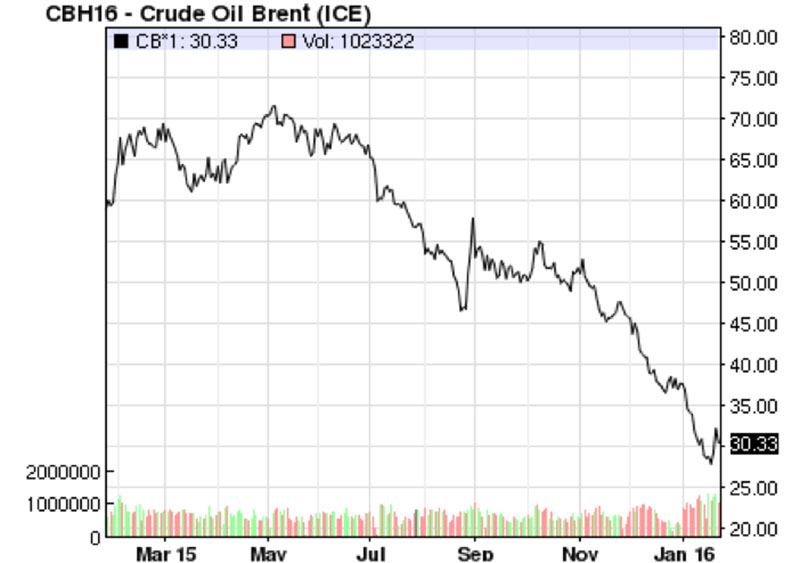

The price of Brent crude has been a major factor in the development of the North Sea for some years. Brent is a sweet, light crude which is used for petroleum and middle distillates and today is a blend of several crudes from a number of UKCS fields. It is used as a benchmark against which other crudes are measured. Since 2004, it has been traded on the ICE exchange and is a leading marker crude.

Its price exceeded US$140 in mid 2008 and was followed by a sharp decline to below US$50 by the end of that year. From early 2009 the price started to climb, rising above US$100 by the end of 2010 where it stayed until mid 2014. Subsequently, there was a dramatic fall in prices to just above US$60 by year end.

During 2015, the price of Brent has varied between US$70 at its height and by the end of 2015 was below US$38. The price per barrel continued falling in January 2016 to below US$28 per barrel. This is creating even more problems for operators who were hoping for better news in 2016. The price had increased slightly on the news of more conflict in the Middle East, specifically between Iran and Saudi Arabia. What does 2016 hold for the industry, ‘Lower for Longer’ is a popular prediction but when did the oil price ever conform to prediction?

Fig 2 – ICE Brent Crude Price for the last year

Courtesy of ICE

A number of analysts believe that this is not the end of large scale job losses if the oil price remains below the US$50 price. It is anticipated that more job losses will occur as some companies are unable to meet their debt obligations or simply fold as the cost of production exceeds the income stream. During 2016, a number of oil price ‘hedges’ will cease, resulting in income streams dropping further for many producers. It has been announced recently that major companies reported a decline in profits resulting even more job losses.

As a result, the UK is exposed to losing a large number of top class professionals. This will be amplified by the number of senior staff taking redundancies and early retirement losing the industry valuable experience. Aberdeen has borne the brunt of job losses and the near-term future does not look promising.

Over the past few years as high oil prices have been maintained at unsustainable levels, the industry has approved more developments and EOR projects which, in turn, put a strain on the availability of qualified staff globally. The effect was to increase salaries and bonuses to attract staff and retain existing teams. Large sign-on bonuses were paid alongside generous remuneration packages which increased G&A and added to project costs.

A Way Forward?

There is currently a need for urgent action to avoid losing production, fields, infrastructure and expertise that has been built up over decades as low oil prices remain depressed for the near term. Confidence in the sector is essential for investment and to attract new players. The major issues facing the sector are set out below.

Cost Reduction

Much has been stated in the press and in statements from industry groups about reducing costs, working smarter and co-operation but as many within the industry would say, “We have been doing this for years”. A number of companies have made announcements to the effect that they have brought down OPEX costs and are now returning a small profit from these fields.

Reducing costs is an important part of the equation but it is not just the offshore arena where costs can be saved. Reducing the G&A, office costs and utilising new technology are all part of the future when income is lower. The industry had become very heavy in resource costs paying ever higher base salaries and offering significant bonuses and benefits packages.

New and lavish offices, many of which are now under occupied, have been built on the belief that the oil price would not fundamentally change. Working smarter and recognising that every new project does not need to start from a green field thought process should be the norm not the exception. Utilising existing and proven methods, in conjunction with existing designs are cost effective and usually more reliable. Re-inventing the wheel which requires longer lead times and greater investment has been part of industry life.

This is not the first time that the UK has endeavoured to reduce costs. In the 1990s, we had the CRINE initiative (Cost Reduction in the New Era). This was heavily promoted by companies and government bodies and was followed by further schemes to keep costs low and share information. Sadly, when oil price rises, memories are short.

Another scheme is PILOT which was established some years ago and evolved from the Oil & Gas Task Force. PILOT facilitates the partnership between the UK oil and gas industry and Government. It did not foresee the problems of low oil price and was as unprepared as the industry for the dramatic changes caused by the price slump.

Contractors also need to recognise that they are part of the equation and need to reduce prices if they wish to retain their workforce. One industry professional speculated that “prices in Aberdeen need to fall by between 30% and 40% for the industry to keep working”. The service industry has also been shedding staff while it reassesses the true need for resource against client requirements. The operators and partners need to work closely together to achieve the optimum development and recognise that both need to make a profit to remain in business. It is within this area of collaboration and co-operation that significant cost savings will be found.

Production

As the following graph shows (Fig 3), UK production has been declining for some years. However, in 2015/16 production is expected to increase slightly.

How long can significant production continue as the decommissioning of older and non-profitable fields starts to impact the nation’s supply?

The danger for the near-term future is that new developments will be stalled or shelved until prices rise again, thus causing significant dips in production.

As the infrastructure of many of the older fields reach the end of planned life and maintenance costs increase, operators need to look to new technology and ‘best in class’ operations to reduce costs and maintain or raise production. The Wood report stated that operators needed to explore ways of extracting the maximum from each field and the OGA is looking for operators who will maximise economic recovery – so, every option must be explored and shared with others to bring about the changes required for a stronger industry that meets the challenges of the low oil price environment.

In some cases, smaller operators could look to:

(i) Merge operations where assets are in close proximity thus reducing costs

(ii) Develop smaller fields ‘smarter’

(iii) Monetise stranded assets by providing easy, economic access to infrastructure

The above actions could reduce waste, maximise recovery and keep some of the smaller fields producing profitably. To promote this idea would need significant co-operation at board level to ensure that the new entities have the best people leading their growth.

On the subject of infrastructure access, perhaps the newly established Oil & Gas Authority (OGA) should be the arbiter to persuade companies to share, at economic prices, their facilities, thus enabling longer term production with lower costs. This could have the effect of extending the life of some fields as well as bringing on-stream ‘stranded’ fields that would otherwise remain dormant.

In a white paper published by the Offshore Network, it identified that there were over two billion metric tons (c.14 billion barrels) of oil remaining in reservoirs of produced and producing fields on the UKCS. These figures are derived from numbers published by DECC stating that average oil recovery was 66% and that 3.3 billion metric tons had been produced between 1975 and 2013.

If the industry, in collaboration with the service sector, could increase recovery (cost effectively) by small percentages, this would improve levels of production. This is where effective reservoir management and surveillance combined with production optimization and EOR projects could make a real difference.

However, it should also be noted that, if new fields are to come on-stream over the next decade, then exploration activity must continue. The danger of the low oil price environment is that exploration drilling will slow or stop resulting in the pipeline for potential new fields being empty. This will inevitably cause a ‘mad –dash’ when prices start to rise and repeat the boom and bust cycle of the oil industry.

Figure 3 – UK Oil & Gas Production 2004 – 2014

Courtesy of DECC

Collaboration

Is there a new way of looking at the development and future investment for the UK North Sea?

An important issue is the number of players and the lack of co-operation, so is there a case for regional operators allowing for economies of scale through one supply chain thus reducing costs and increasing efficiency?

Operators need to appreciate that increased competition is not necessarily the answer in operations. One commentator recently stated that “…the most important time period when oil companies have a competitive advantage is during licence round application. Once these are complete and the winners of the assets are confirmed, where is the competition?” So why not share much more information in the operating arena? Is this anti-competitive or could it be one of the elements saving the future of the UK North Sea?

Maximising cost recovery from JV partners and structuring supplier contracts to minimise budgeted costs is great for the operator but these actions do not promote collaboration nor the sharing of business risk. There needs to be a change of view, from competitors to partners thus helping to grow knowledge and efficiency.

In a recent survey of oil companies and oilfield service companies, Deloitte stated that “a lack of effective supply chain collaboration means that companies are missing out on maximising the potential value of the UKCS”. They went on to say “the most critical finding highlighted the discrepancy between what drives successful collaboration, and the actions of leadership and business process to underpin it. Whilst there was clear recognition of the value of collaboration and what’s needed to make it happen, trust and mutual benefits for example, less than 10% said that leadership regularly emphasised its importance or included it in their business strategy”. Commenting on the Deloitte report, Oil & Gas UK said “Collaboration is crucial if we’re to fulfil Sir Ian Wood’s vision to maximise economic recovery from the UK Continental Shelf”.

Investment

Investment is imperative for the long-term future of the sector. Will Private Equity firms play a more important role as investors look for new opportunities to invest whilst interest rates are low?

We have seen in the press recently a number of PE companies funding new companies to take advantage of the low oil price effect on asset values. This is based on the premise that prices will rise again but when? General consensus suggests that oil prices are expected to remain low throughout 2016 with some increase appearing in 2017 but will this be too late for some?

There will be more casualties and more job losses over the coming months but, on the positive side, industry will become more efficient. Private Equity will fund management teams that have a proven track record and a good business plan. Also, some new players will enter the market to work in niche plays with problem fields. If changes are made to the fiscal regime, more players will consider investing in fields and potential exploration programmes.

In general, Private Equity has looked at investment in the oil sector as short-term whilst the industry needs long-term investment for long-term field development and maximising recovery. If investment is short-term then development strategies tend to be short-term leading to lower recovery rates. Perhaps now is time to rethink the investment strategy to provide for the longer-term

The need for cutting costs and improving efficiency will inevitably drive some companies to look at mergers and/or acquisitions to increase value and lower costs. The sector has a number of players with good assets but no cash and whose options, in consequence, are limited. Merging may be one answer to help these companies ride out the storm of low oil prices.

Consolidation

The need for change in the industry goes without saying but can these changes be made quickly enough? The danger is that whilst dialogue continues, we lose production from fields that are uneconomic and unlikely to be re-drilled when the prices rise. In addition, we lose significant numbers of highly skilled professionals who are unlikely to be tempted back to the industry. Furthermore, we lose investor confidence that hastens the demise of the UK North Sea.

Exploration needs to continue to ensure a pipeline for the coming years to keep both sides of the industry active. Service companies need to work closely and collaboratively with the operators to produce more efficient and cheaper operations resulting in a healthier industry. The regulators and Treasury also need to provide stimulus to ensure that activity continues and the security of supply is maintained. The United Kingdom Continental Shelf has an economic future but all parties concerned must play their part in delivering its continued success and the necessary actions need to be initiated now.